Winter Fruit

Nelson Henricks

November 20 - December 23, 2020

Paul Petro Contemporary Art is pleased to present exhibitions by Nelson Henricks and Michael Morris.

Henrick's latest work, Winter Fruit, expands on the work found in his last exhibition, Lacuna (Alas Poor Yorick!), by diversifying, across several mediums, his references to the lacuna in architecture and the black page found in Lawrence Sterne's Tristram Shandy (1759).

Brought into juxtaposition with City Deluxe, an assemblage of printed works by Michael Morris from the 1967-1972 and a suite of etchings from 2012, the exhibitions open up a dialogue on abstraction that crosses generations between artists and reaches back, via Josef Albers, to Sterne's time.

lacuna

an unfilled space or interval; a gap.

a missing portion in a book or manuscript.

My mother was an artist. When she died in 2015, I inherited her leftover paints. She often said we should paint together. This was something we never did.

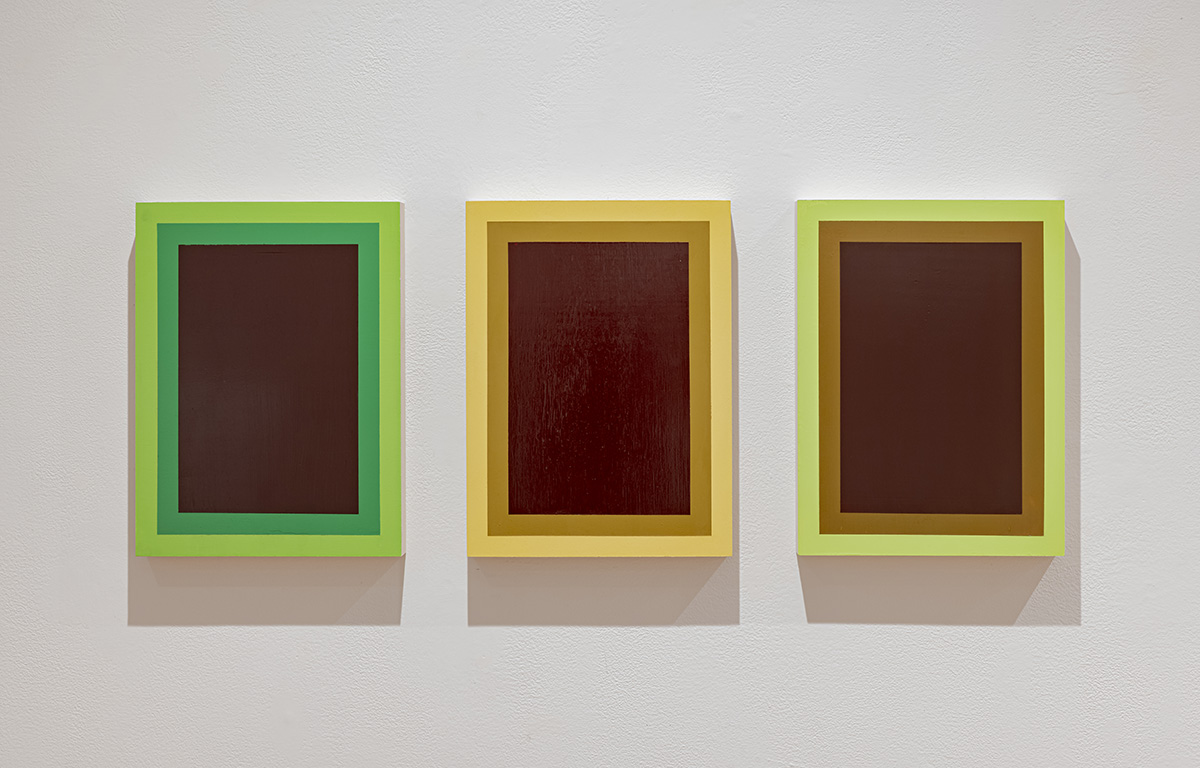

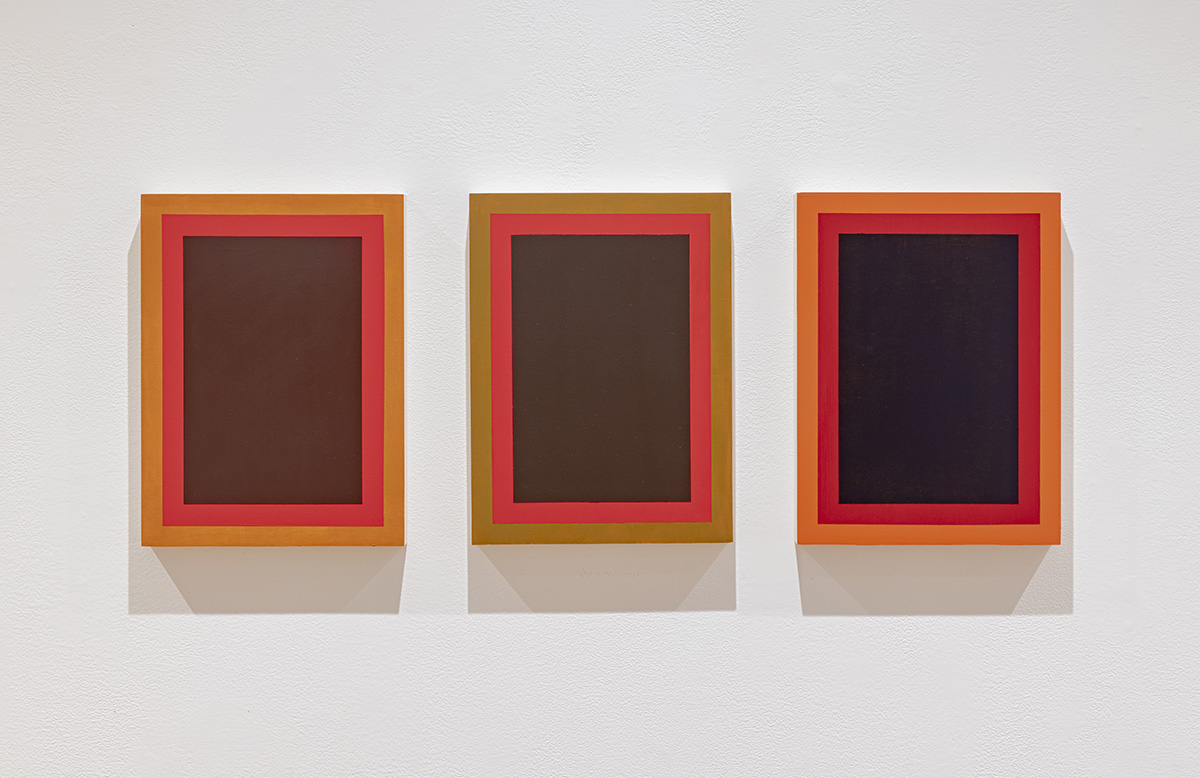

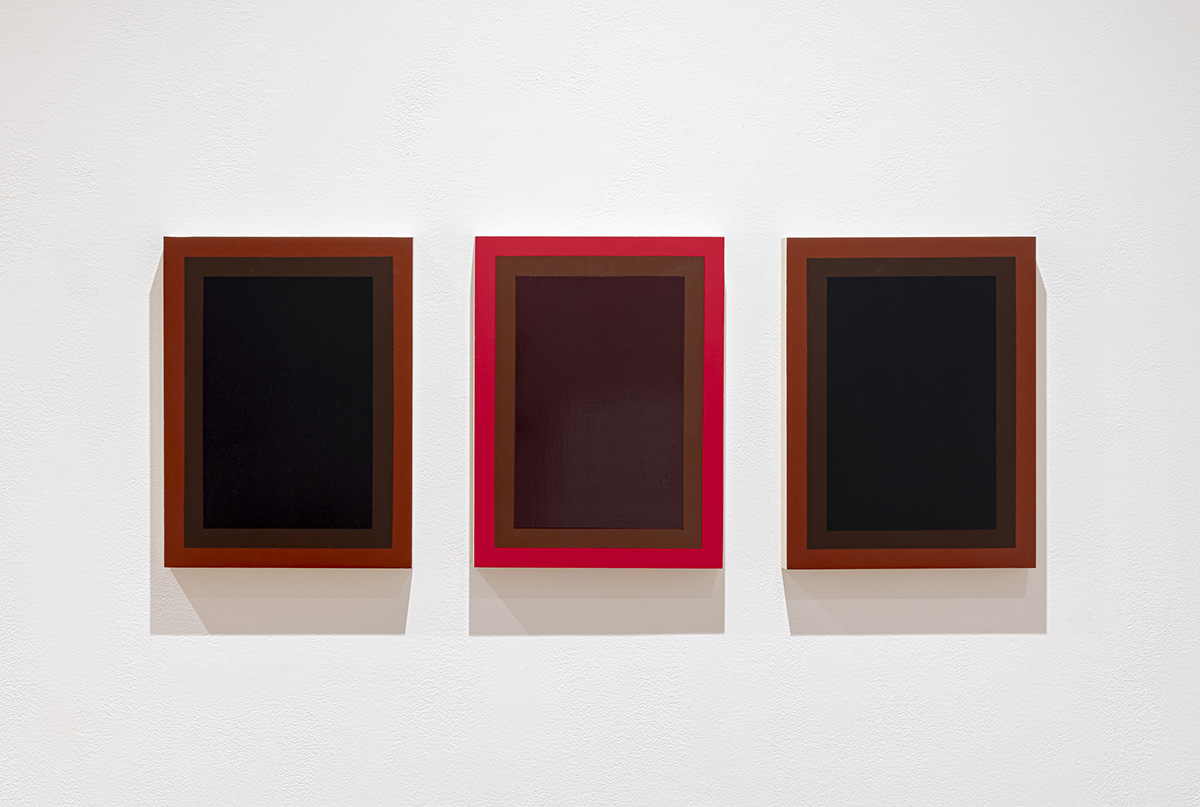

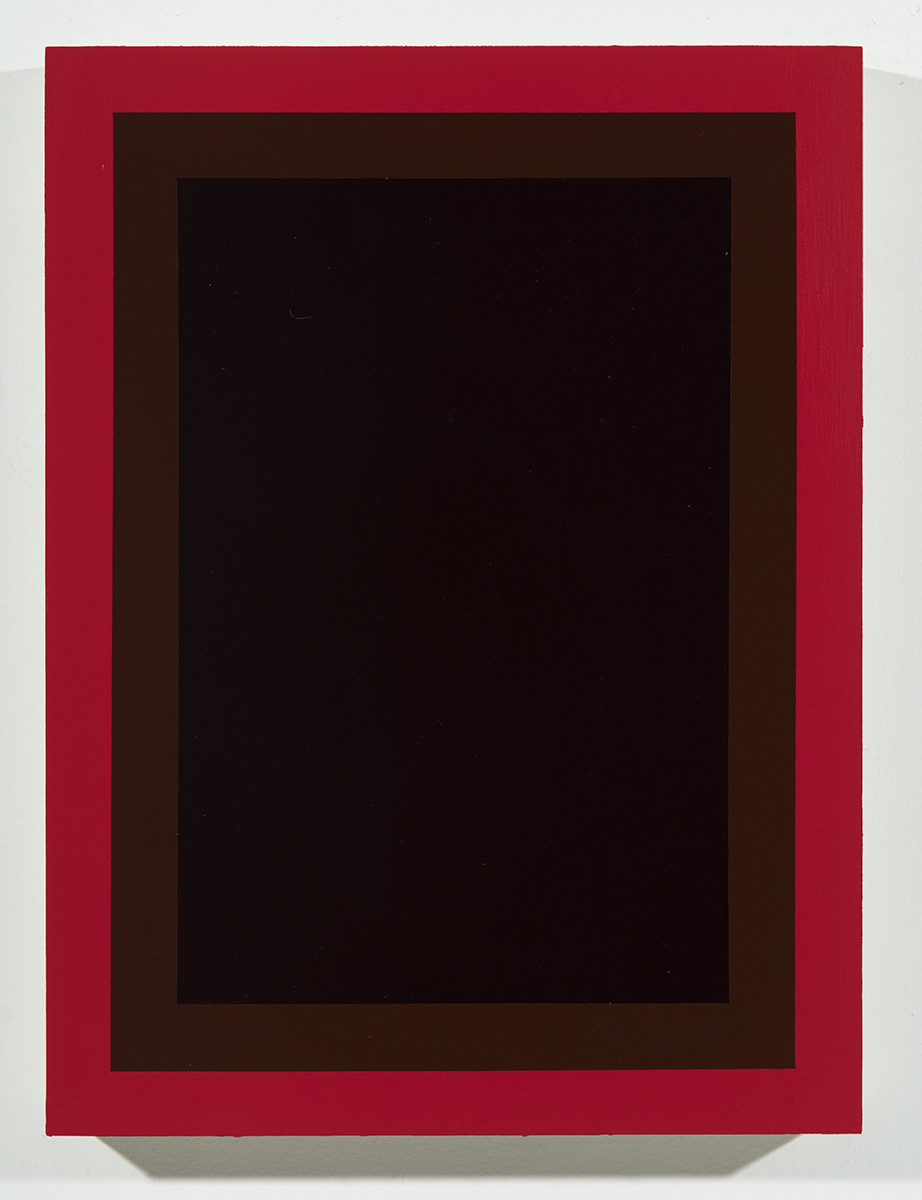

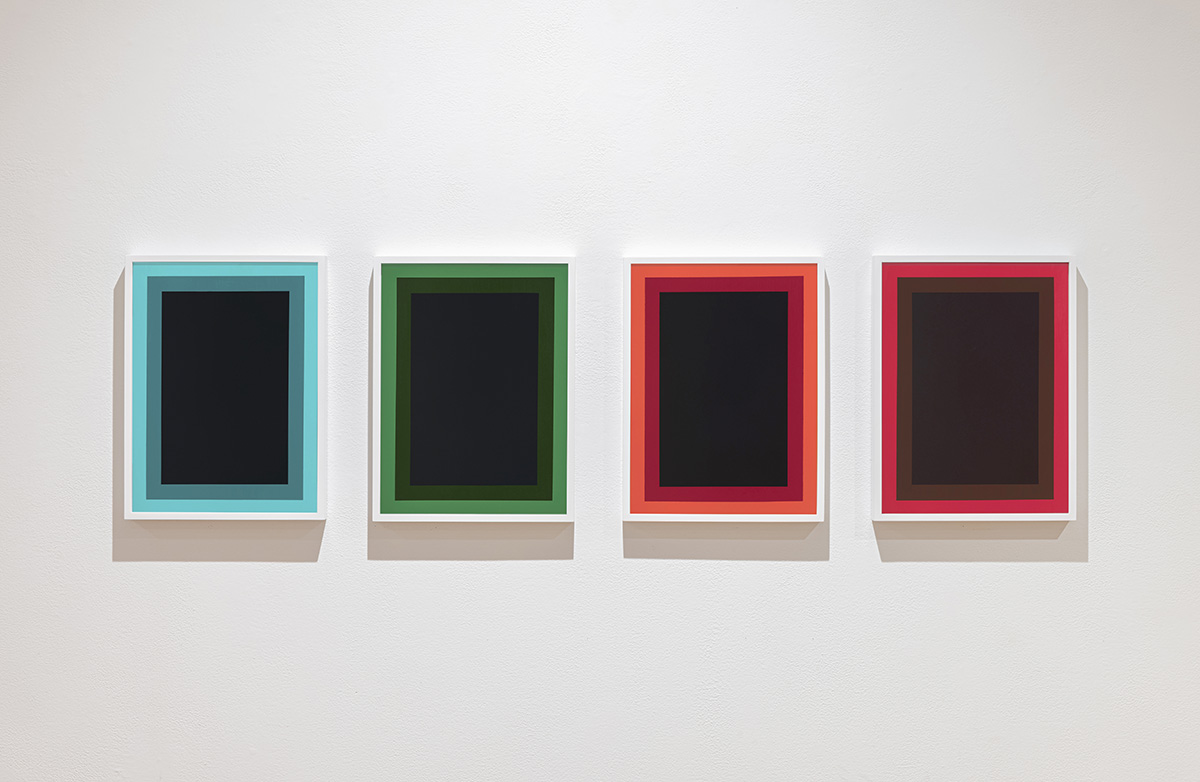

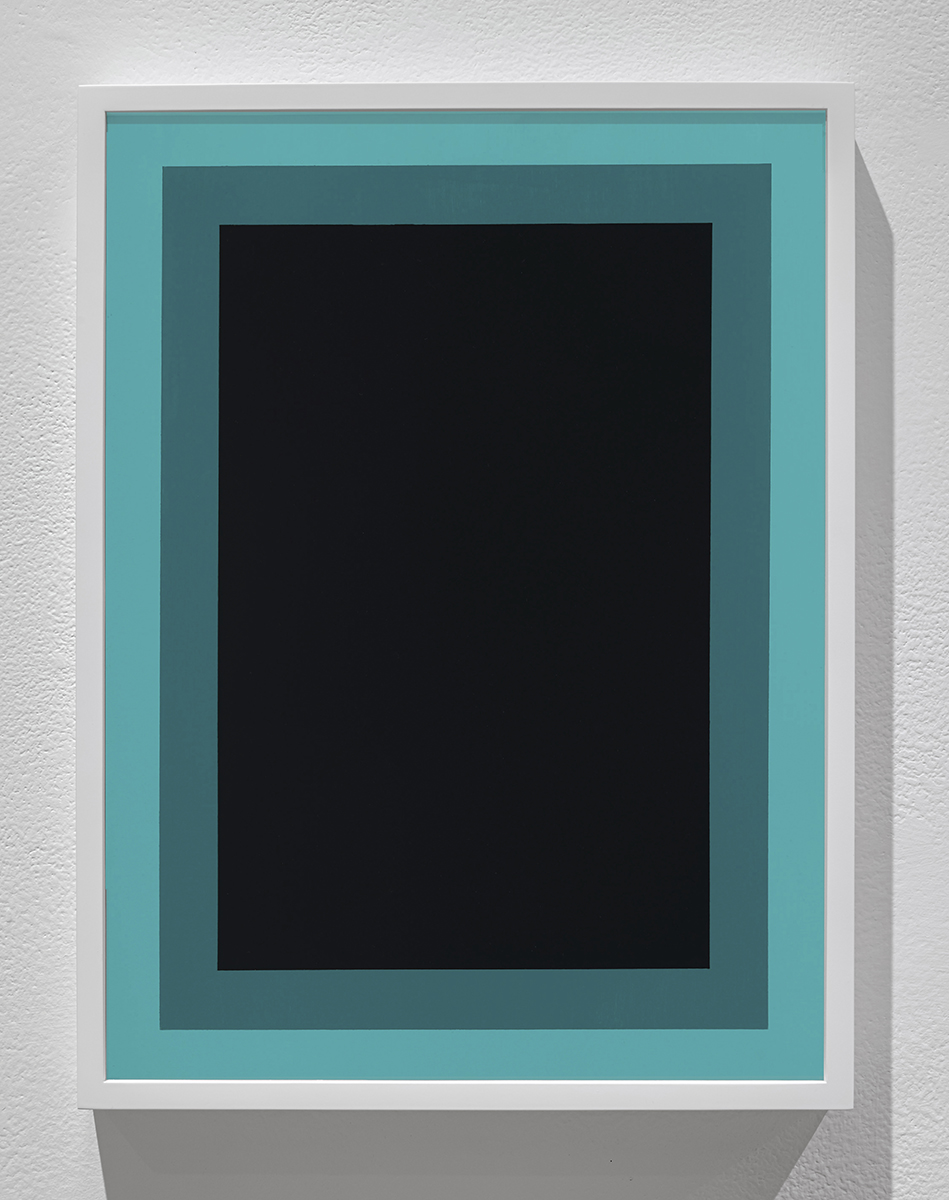

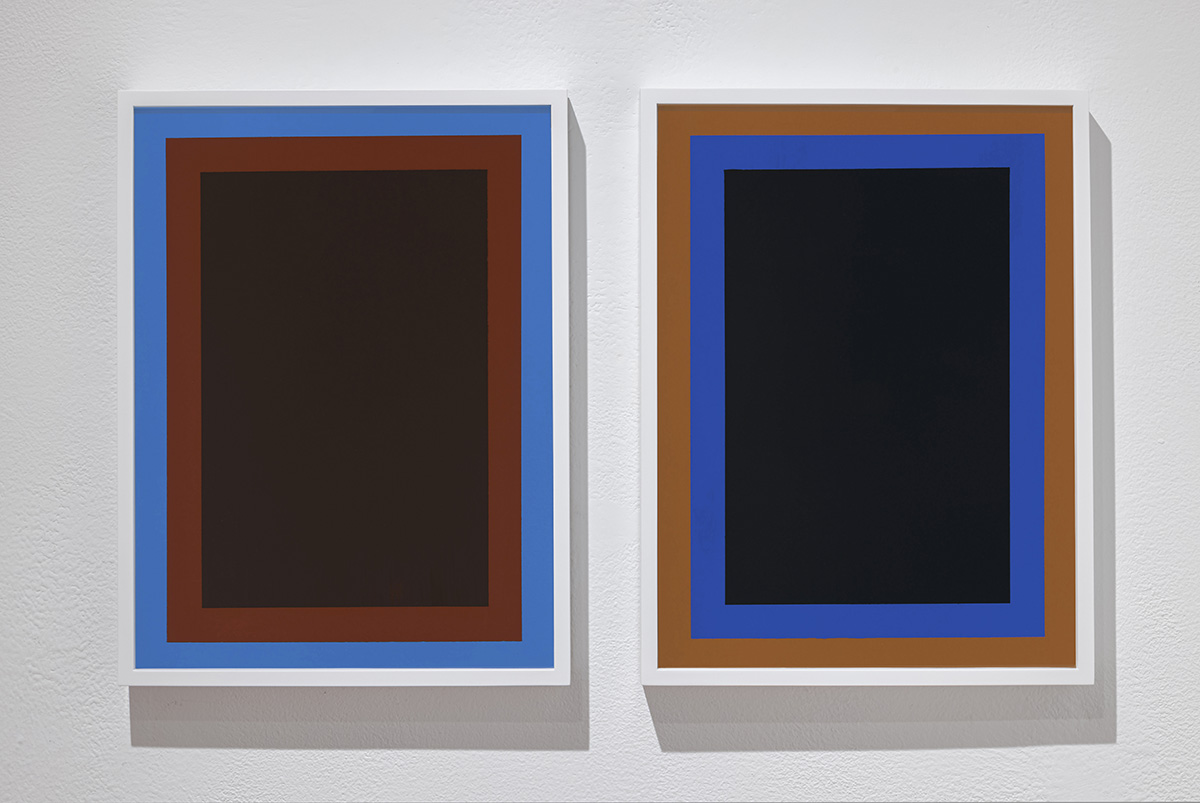

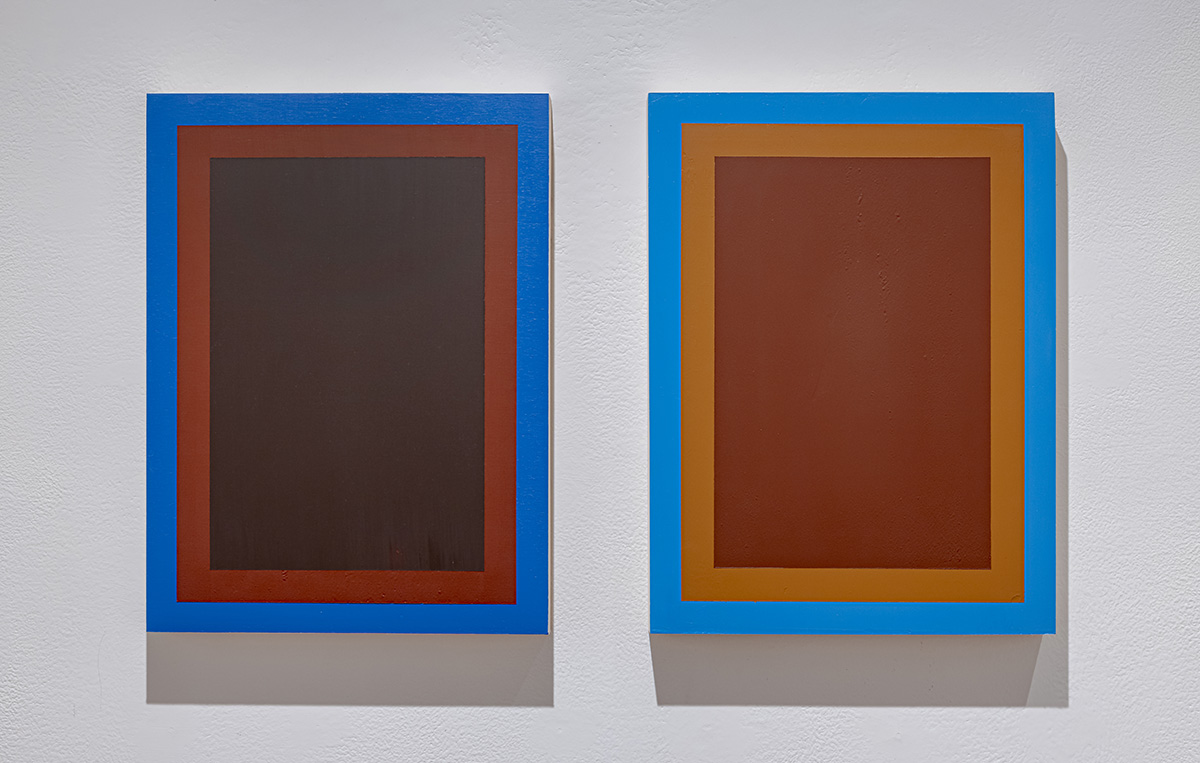

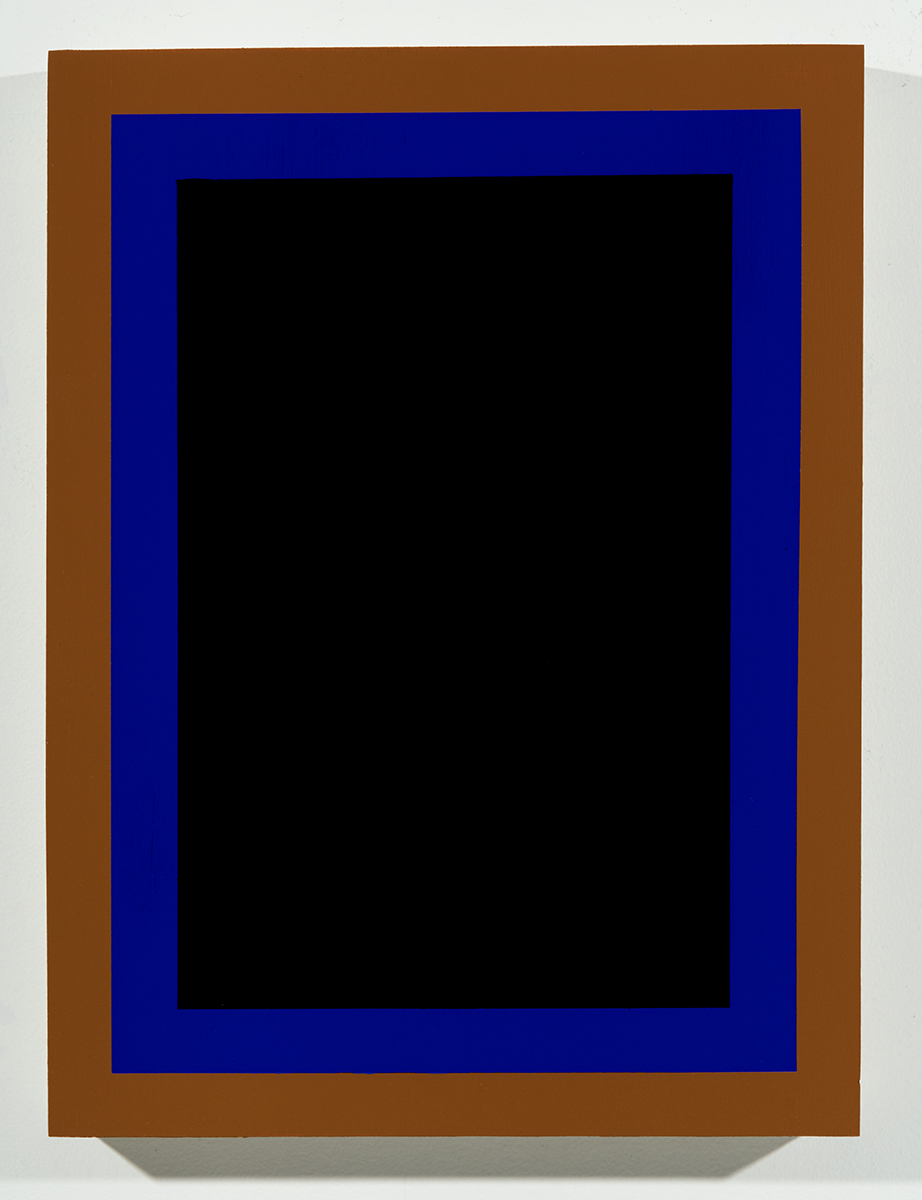

Later, during a six-month residency in New York in 2017, I began working with a visual motif––a rectangular frame within a frame. Due to its resemblance to coffered ceilings in architecture, I called it a lacuna. The framed absence embodied a paradoxical fluctuation between absence and presence, between excess and nothingness. Like a double negative in language, it seemed to cancel itself to produce an affirmative, while at the same time intensifying the initial negation.

It occurred to me that Mom’s paints––both for their plastic qualities and emotional resonance––would be the perfect material with which to develop a series of paintings based on this motif. Her tubes of colour were part found object, part affective Readymade, and would charge the paintings with an expressive value that would nonetheless remain intangible.

Returning to Montreal in early 2018, I embarked on a two-year process that led to the production of approximately 70 paintings. The lacuna motif was reproduced in various colour combinations and sizes in an attempt to exhaust my mother’s paints. Though the paintings are bound to the history of abstraction, they nonetheless function as representations. Seen together, they are an averaging of my mother’s colour preferences. They also act as a stand-in for her unfinished work: the paintings that she might have made had she lived longer. They are mirrors, they are holes; they are pages torn from a book, frames of nothing.

A few years ago, I was researching artist studios and studios that are preserved in museum contexts. Daniel Buren’s text The Function of the Studio (1971) describes the crucial link between the artwork and the site of its production. I see the artist’s studio as fulfilling several roles: one of them is as a research lab. The half-sized model becomes a representation of the studio as a site for knowledge production. It is also a framing device for the small-scale lacuna paintings I made in parallel with the larger ones. Like a mise-en-abyme, the sculptural model is a frame for framing empty frames.

One of my aims with the Lacuna project is to question traditional understandings concerning the relationship between originals and copies. I am drawn to the notion of the artwork as a network. I try to draw emphasis away from the unique object, and instead point to the artwork as a non-hierarchical, lateral sprawl whose individual parts mutually reinforce one another. This reach extends backwards to my mother’s painting practice, and forwards to explorations in photo-based media.

Nelson Henricks, August 2020

In the preceding exhibition from 2019, Lacuna (Alas Poor Yorick!), Henricks brought together a series of works in diverse media inspired by the black page in Laurence Sterne’s book The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

Tristram Shandy is a farcical autobiography published in nine volumes between 1759 and 1767. The novel is highly experimental, exploring the limits of typography and print design. For example, in Book 1, Chapter 12, a page printed entirely black appears at a point in the story when a character named Yorick dies. On one hand, the black page can be understood as an overflowing of ink and emotion representing inexpressible grief. On the other hand, it is like an image of an open grave: an opening, an absence, a void.

Using Sterne’s black page as a starting point, Henricks developed two series of paintings, two series of photographs, and several mixed media works. On one level, the project is an exploration of the history of modern art. Sterne’s black page both predates and anticipates 20th century monochrome, a history that traditionally begins with Malevich’s paintings Black Square (1915) and White on White (1918). Henricks excavates a prehistory of monochrome, one that originates in farce, rather than in formal or spiritual concerns.

Found in these related bodies of work lie several intersections with Michael Morris, whose practice dates back to the 1960s. Morris references 20th century painting and architecture with allusions to the monochrome of Josef Albers and the architecture of Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau amongst others, adding another source with the geometric patterning found in Busby Berkeley musicals.

Curator Scott Watson has famously described Morris’ work as being painted by the light of the cinema lumière. The artifice implied by this antithesis to northern light points to the staged theatrics and the film noir tone found in Morris’ work and suggests the queering of abstraction he has undertaken.

In Morris' exhibition City Deluxe, showing concurrently with Henrick's Winter Fruit, there is a suite of etchings from 2012 that originated as drawings produced in 1968 and have motifs which extend into silkscreened prints and posters also found in the exhibition. It is here that we find the allusions to Busby Berkeley and a site where the world is a stage, and where the glamour of Old Hollywood and camp converge. And it is here that we encounter the seemingly coded aesthetics of concrete poetry, where the eye learns to see image meaning while trained to look for words, like the secret door found in the wood panelling of a home library or the key to a heart.

Working ideas across several media is common to both artists and informs their concepts about research. In the case of Morris there are more than forty years of ongoing Colour Research which inform much of the Morris/Trasov archive and remains a dominant exploration in his work (we considered colour bar research in his survey exhibition in 2018). And with Henricks we have a succession of Lacuna-inflected exhibitions that explore the site of production (the studio) and the site of exhibition (the gallery).

To this end Henricks and Morris share a polychromatic colour spectrum pursuit and their exhibitions disclose the elongated effects of their research and lab experimentation, and that which resides "off-stage" in the shadows of chance and repetition, or, as Henricks smaller-scale maquettes and wallpaper suggest, in urban home decor.

NELSON HENRICKS was born in Bow Island, Alberta and is a graduate of the Alberta College of Art (1986). He moved to Montréal in 1991, where he received a BFA from Concordia University (1994), and a PhD at Université du Québec à Montréal (2018).

Henricks lives and works in Montréal, where he has taught art history and video production at Concordia University, McGill University, UQAM and Université de Montréal. A musician, writer, curator and artist, Henricks is best known for his videotapes and video installations, which have been exhibited worldwide. A focus on his video work was presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as part of the Video Viewpoints series in 2000. His writings have been published in exhibition catalogues, magazines, and in several anthologies. Henricks was the recipient of the Bell Canada Award in Video Art in 2002 and received the Board of Govenors’ Alumni Award of Excellence from the Alberta College of Art and Design in 2005. A mid-career retrospective of Henricks' work was presented at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery in Montréal in 2010.

Henricks’ work can be in the collections including the National Gallery of Canada, the Museum of Modern Art (New York), Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal, the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery and Banque Nationale du Canada.