New Grapes

André Ethier

paintings

July 17 - August 15, 2015

"With art school behind him, André Ethier touched down in Toronto shortly after the start of this new century and soon had most of what he needed to launch a painting career.

"He found comrades and a psychic home, for instance, in the anarcho-bohemian art, music and party scene headquartered in Kensington Market and the galleries and clubs of Queen Street West. He discovered suitably dissident exemplars among the artists of the millennial moment, including Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy and Raymond Pettibon in California, and Peter Doig everywhere.

"Like Kelley, Ethier sang and played guitar in a garage-rock band while, again like Kelley, making images that showed no respect for the elite, prim art world pieties prevailing in North America and Europe during the ascendancy of neoliberalism. Rock was said to be dead, and so was painting, he recalls, but he rocked and painted anyway, and generally minded his own business at a time when minding other people’s business was in style. He was having nothing to do, in any case, with feminist orthodoxies, identity politics or the academic traffic in big ideas, or the high-polish Conceptual photography on the walls of every contemporary art museum in the world at that time, or with painters who created work that looked like photographs." -- John Bentley Mays, Canadian Art, Winter 2014.

André Ethier (born 1977, Toronto) is a Toronto-based painter and musician. He attended Etobicoke School of the Arts for Visual Arts and received a BFA from Concordia University in 2001. Ethier has exhibited extensively in Canada, the U.S. and Europe. He is represented in New York at Derek Eller Gallery and has an upcoming exhibition in October 2015. New Grapes is Ethier's second solo exhibition at PPCA.

André Ethier at Paul Petro Contemporary Art, Toronto

John Bentley Mays

As recently as early 2014, when André Ethier last showed his oils at Paul Petro, the small oblongs of Masonite could still, on occasion, be awful in an intriguing way, like the behaviours of Freud’s Rat Man--puzzling, crudely libidinal, obsessive, screwed up. But by then the artist had begun to curb the aggression and oddity that previously fuelled his painting project. He had acquired a new resource, Matisse, and his art was becoming “kinda French”--a phrase he uses for both himself and his product--and being softened and de-kinked by Mediterranean breezes.

With New Grapes, Ethier’s summer, 2015, display at Paul Petro, this transfiguration of his painting’s sense from raw to cooked, from stress to luxe, calme et volupté, was largely complete. The colours were dry and mineral, but fragrant, like scented face-powder. The grape bunches, dense foliage, fruits deposited on fin-de-siècle tables were lush, succulent, at their peak and not even slightly past it. A bearded gentleman--Ethier once told me that all his male figures are self-portraits--relaxed in a flourishing garden. The prevailing atmosphere was sunny and sub-tropical. There was not a cancerous nose or rotting vegetable or livid bouquet in the show, or much else to remind gallery-goers of Ethier’s usual painting in the first decade of this century.

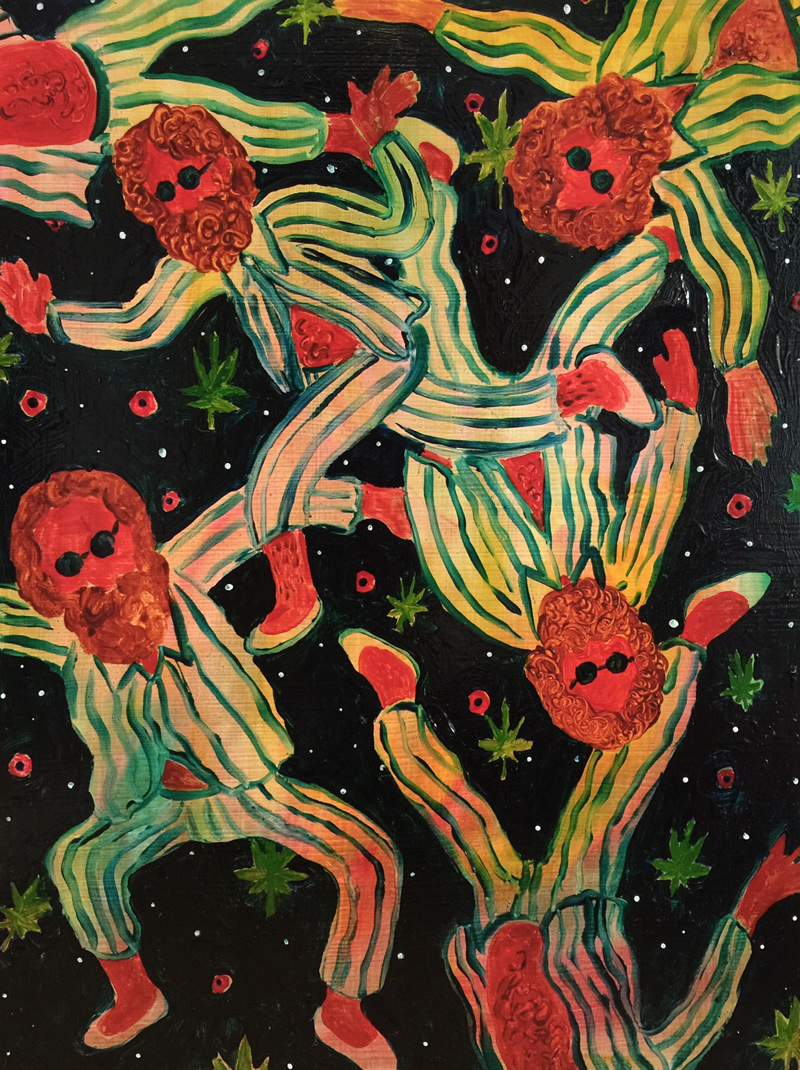

But in a couple of works, a character reappeared from Ethier’s earlier tradition of self-portrayal as urban bum. He is a hairy hobo in dark glasses and dressed in striped pyjamas (or a prison uniform), who is found cavorting in gravity-free space with clones of himself, and, once, lounging improbably, and quite out of place, beside an opulently arrayed table in a fusty parlor.

In the latter painting, the two personae that Ethier has assumed over the course of his 15-year career--the earlier one angry, the later one peaceable; one bitter, the other generously sensuous; one resentful, the other almost respectable--met and recognized each other. If their rendezvous seemed forced and slightly uncomfortable, it was because the painting united in a single frame two sensibilities (or creative strategies for engaging the world--one critical, one decorative) that normally disdain each other.

What is to be made of the change in Ethier’s art during the last few years? Is it--to use a “kinda French” word, since no plainer English one means what I want--so much cultural embourgeoisement? And if so--so what?

Considered as craft and knack with materials, his picture-making has never been better. The best of his compositions are vigorous, profane as a beach holiday, inhabited by modern painting’s durable symbols of heterosexual arousal, including grapes swollen with sap and naked, ripe female bottoms. Were I a more rigorous feminist than I am, or were I an admirer of only those painters who abstemiously reject every inherited conceit and figure, I might dismiss Ethier’s new art because it gladly, unquestionally aligns itself with the sensuously relaxed aesthetic regime of Matisse, and adopts even the topics--still life, the domestic interior, the female figure--that Matisse treated so memorably.

But being neither much of a feminist nor an avant-gardist of any sort, I generally appreciated what Ethier did in New Grapes. In my view, the frank, rapidly but deftly drawn paintings there have earned a noteworthy spot in the heavily crowded field of contemporary artworks that claim to be fertilized by Matisse.

That said, I missed, in New Grapes, the obnoxiousness, the toxic colours and sick cartooning which had interested me keenly when I wrote my 2013 essay on Ethier for Canadian Art. These obstreperous qualities were already disappearing by that time, but enough downright orneriness remained in the work to reward close attention.

At first glance, this orneriness seemed driven by a will to frustrate almost everybody’s expectations about what “good art’ should look like. I do mean everybody: toney formalist and post-modern critics, friends of “normal” painting and fans of photography, art-world leftists and rightists, feminists and the new-media crowd and, of course, your Aunt Harriet. If some writers for the dailies liked Ethier’s neurotic, emotionally wasted pictures, it was probably because, as I and my fellow journalists know, the uppity always make good copy.

But had our curiosity been grinding away in the right gear, we might have hesitated a long moment before visiting either blame or praise on Ethier’s early artworks. For in their bluntness and brashness, in their grating strangeness, these tableaux, portraits, still-lifes, hysterical or desperately banal genre paintings insisted on their right to be given time, to be taken seriously, to be about something. They smelled like the bitter ash of brains burnt out by consumerism, the culture of disposability, mass media’s numbing of affect. They offered glimpses of the ordinary urban world, its things and marginal people, as seen by this century’s citizens, especially young ones, who had been numbed, discarded, exhausted by the seethe of mass culture.

At least I think it’s mass culture that did them in. Perhaps I am merely projecting onto this art my own theories and preoccupations. For his part--in the painting itself, I mean--Ethier declined to identify the forces that had infected his times with dry ennui, hungover torpor. Instead, throughout the years before his adoption of Matisse’s manner, he created a series of pictures--some of them unforgettable--that document a despairing spirituality common enough in the urban West. If he found no cure, so be it: painters do not need to be saviours. What he did--the art and evidence he made and showed--was good enough.

-- John Bentley Mays, August 2015, www.johnbentleymays.com